‘His Adopted Daughter’: How the Media Tells Dylan Farrow’s Story

There's a tendency in our society to think of relationships formed by adoption as somehow less real than those rooted in biology. This may explain why so much of the discussion of Farrow's story of abuse has focused on her status as an adopted person.

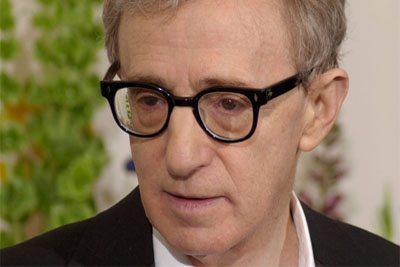

“For as long as I could remember,” writes Dylan Farrow in her widely discussed letter that appeared Saturday on the New York Times website, “my father had been doing things to me that I didn’t like.” She refers to him, celebrated filmmaker Woody Allen, as her father, without qualifier, because that’s exactly what he is.

Why does so much of the discussion of Dylan’s story of abuse, then, focus on her status as an adopted person? Nearly all coverage—both in support of Dylan and in defense of Allen—describes her in headlines as Allen’s “adopted daughter.”

Mia Farrow adopted Dylan in June of 1985, when she was an infant. (Mia had six children from her earlier marriage to Andre Previn—three biological, three adopted—and another son that she had adopted with Allen; after adopting Dylan, she would give birth to one more child—a son, Ronan, with Allen—and adopt six more on her own.) Court records show that from the time Dylan joined the Farrow family, Allen became more engaged with the family, visiting their homes in both New York and Connecticut more often, joining them on family vacations, and gradually adopting a fully paternal role, culminating in December 1991 when he legally adopted Dylan and her older brother, Moses. Around that time, he also abused her, she says, and entered into a sexual relationship with her older sister, Soon-Yi.

Woody Allen became Dylan’s father, first in practice, and then on paper. Yes, Dylan has another father (and, indeed, another mother, in addition to Mia Farrow), but it’s undeniable that Allen played the father role from the very beginning of her life.

I have written before about how important inclusive, appropriate language is when discussing adoption, in order to acknowledge the roles that different parents can play in one child’s life. And, yes, of course Dylan was his adopted daughter; it is not inaccurate to say so. But this diction is not being deployed as a way of examining the dynamics around adoption, or as a way of acknowledging the place of Dylan’s birth parents. It seems that the only reason to include this qualifier then is to stress the lack of genetic relationship between Allen and Dylan. Why? Does the removal of the incest taboo somehow make the alleged sexual abuse of a child less horrific, or more acceptable of a topic for public debate? If Dylan were perceived as Allen’s biological daughter, would his defenders squeamishly keep their silence? If the headlines blared instead, “Woody Allen’s daughter accuses him of sexual assault,” would we feel differently about the case? The fact that Dylan is adopted should have no bearing on our understanding of the case or our judgment of her story. It should be entirely irrelevant. Yet, its consistent inclusion insists that we must examine it.

The missing narrative here is that of Soon-Yi Previn. Soon-Yi was adopted by Mia Farrow and her second husband when she was around 6 years old (her exact age is unknown). She was around 8 years old when her mother began her relationship with Woody Allen, and around 20 when she began her own with the filmmaker. Allen’s defenders go to great lengths to clarify that Allen did not have a paternal relationship with Soon-Yi (primarily supported by a reference to Soon-Yi’s ongoing relationship with Previn, as if that could have prevented Allen from assuming an additional fatherly role to the young daughter of this partner), to reaffirm that Soon-Yi was an adult when their relationship began, and to stress that Soon-Yi was the adopted daughter of Farrow. Even viewed in the most sympathetic light for Allen, the facts remain that he began a sexual relationship with a young woman 35 years his junior, whom he had known since she was 8. As recently as 2011, he seemingly shrugged off a reporter’s question about their relationship, asking, “What was the scandal?” If Soon-Yi had been the biological daughter of Allen’s long-term partner, and the biological half-sister of Allen’s children, would this be perceived differently?

It seems the public is more willing to accept this premise—that Allen didn’t have a familial, let alone paternal, relationship with Soon-Yi when she was a child—than they would if genetic ties were in play.

This acceptance was expressed concisely in the Daily Beast by Allen defender and filmmaker Robert Weide. Responding to Ronan Farrow’s oft-quoted line, “He’s my father married to my sister. That makes me his son and his brother-in-law. That is such a moral transgression,” Weide wrote that “this particular dilemma might be resolved” by Ronan’s disputed paternity. (Mia Farrow has said that Ronan may be the biological son of Mia’s ex-husband Frank Sinatra, rather than Allen’s biological son.) Because if Ronan is not biologically Allen’s son, then it does not matter that he helped parent Ronan and later married Ronan’s sister? It seems that such arguments are predicated on the idea that relationships formed by adoption and the act of parenting are somehow less real than those rooted in biology.

It is clear, however, that Allen and the Farrow family don’t perceive of their relationships in this way. We know that Dylan identifies Allen only as “my father,” and that her brother Ronan refers publicly to both Dylan and Soon-Yi simply as “my sisters.” Likewise, Allen signs letters to Dylan as “Your Father,” according to Dylan, and Mia Farrow refers to her entire brood as “my children.” Like most families in the United States formed by adoption, they don’t feel the need to constantly clarify that their relationships did not originate in biological relationships. Furthermore, Allen fought not only to prevent the annulment of his adoptions of Dylan and Moses, but for custody of them both. For him, Dylan is his daughter, without caveat. (Mia Farrow’s attempt to annul Allen’s adoption of Moses and Dylan after the allegations of abuse could be interpreted as a statement of perceived impermanence of adoption. Those who believe Dylan’s allegations, however, should view them in the light of a protective mother trying to legally sever an abusive relationship by any means necessary.) Assuming we believe Dylan’s story, this attempt to remain her father in all ways does nothing to absolve him, but it does show us that the focus on Dylan’s status as an adopted person is not something furthered by any of the primary players, but something imposed on the story by the media.

But how does Allen’s relationship with Soon-Yi, and the media-imposed adoption-centric framework, inform our interpretation of Dylan’s story? Psychological research has shown that disgust is a powerful and unreasoning force, particularly when that disgust is related to bodily violations and the transgressions of sexual norms—which include, of course, both incest and pedophilia. Those who defend Allen’s relationship with Soon-Yi must address both of these concerns, stressing that 1) she was not his daughter, or adopted daughter, or step-daughter, or the biological daughter of the woman with whom he was partnered, and 2) even though her exact age is unknown, she was over the age of 18 when their relationship began. Thus, however inappropriate or scandalous his relationship with Soon-Yi was (or is), both taboos can be reasoned away if one feels motivated enough to do so. For Dylan, the pedophilia taboo only goes away if we don’t believe her, but perhaps the incest taboo can be mitigated, made somehow less disgusting, if her adoption becomes an ever-present part of the narrative. Conversely, perhaps the argument is that lack of a biological relationship meant that Dylan has less capacity to appeal to Woody’s paternal desire to “protect one’s own.” Both of these are absurd presumptions, undermining completely the idea that sexual abuse is based on power, and that molestation is an intense betrayal of the father-daughter relationship regardless of how that relationship began (not to mention an insult to many loving, protective adoptive parents). But maybe in the media’s telling of the tale, the reminder that Dylan was adopted makes it so slightly less egregious that we, as a public, might so freely dismiss her memories, or so readily believe she’s been turned against her father by a manipulative mother, or so swiftly shift the question to “the art or the artist?” rather than maintaining a focus on resolving what may have been done to her and so many others like her.

Ironically, while it seems Allen’s apologists find some utility in repeatedly reminding the public that Dylan is his adopted daughter, they also call on his status as an adoptive father (to the daughters he has adopted with Soon-Yi) as a further defense. Weide, once again, writes:

Anyone who has adopted is familiar with the vetting process conducted by social workers and licensed government agencies charged with looking out for the child’s welfare. Suffice it to say, the case of Woody and Soon-Yi was no exception, especially considering the highly-publicized events of 1992-93. Both adoptions, in two different states, were thoroughly reviewed by state court judges who found no reason why Woody and his wife shouldn’t be allowed to adopt.

Weide is neglecting at least two very important points: firstly, that adopted children are very often at risk for abuse, abandonment, and adoption dissolution, as are their counterparts in foster care—all indications that not all adoptive parents are as vigilantly investigated or assuredly safe as children deserve—and secondly, he does not acknowledge that Allen’s abundant privilege could facilitate the adoption process. Indeed, most adoptive parents benefit from socioeconomic privilege (especially when compared to their children’s families of origin), and Allen further benefits from his celebrity (which has been criticized for easing the adoption process for other famous adoptive parents). Those who use Allen’s later adoptions as evidence of his suitability as a father and as a basis for challenging Dylan’s accounting of events are standing on shaky ground indeed.

It seems like a very dangerous thing, then, to continually reinforce that Dylan is an adopted person. It simultaneously calls on several outdated ideas, specifically that adopted children are tainted by some (real or, often, imagined) failing of their families of origin or circumstances of their birth, that adoptive parents are necessarily more suitable and selfless by virtue of how they become parents, and that the adoptive parent-adopted child relationship is different from other parent-child relationships in a way that makes it somehow inferior. (I do believe that adoptive families are different in ways that should be acknowledged for the benefit of all people involved in the adoption, but I do not believe those differences make them inherently lesser relationships.)

These antiquated biases around adoption are rooted in a history of power imbalance, secrecy, and coercion—the same biases that feed a sexually abusive father-daughter relationship. In order to fully examine the trauma that Dylan says she experienced, we must acknowledge the intersecting issues of adoption and examine why the media continues to call on this framework.